Chaos with a Spreadsheet

Or, how I draft a book.

The sensationalist way to describe my drafting process is:

- I don’t complete a first draft

- I never draft in order

- I never draft from outline

- My work constantly surprises me

- …And, yet, I never get writer’s block

Now that you’re solidly not on my side, here’s what this actually means.

Draft 1

Joyous chaos

If you define a first draft as a manuscript you can read front to back without bumping into [tktktktk tense confrontation scene], it just takes me a while to get there, and I get there with a relatively clean set of scenes. They may not be in quite the right order, but the energy is generally high.

What I consider my first draft is far from readable. I typically have a beginning, an end, and roughly only 25–30k words in between. The lines between draft 1–3 are malleable. They are more a set of milestones than a readable, ‘finished’ manuscript someone could actually get through end to end. Stuff is still congealing, sections are missing all the way until I’m done with draft 3 or 4.

Early drafting is entirely to figure out what I am writing and why. I’m always exploring something that cuts me deep. I can’t help it. I tried to write a jaunty book about a spy and got a treatise on intergenerational, matrilineal trauma shaped by war. I tried to write about the Chosen One and got a story about her 30-something anonymous granddaughter, and the fractious society she lives in.

Forget the ‘planner or pantser’ dichotomy. Do you tense up like a fish in a net when someone says, ‘my characters are always surprising me’? Mine sure do. They appear in corners or leave scenes before I plan for them to. They delete themselves, take on extra meaning, fight about nothing. This is probably because I live in a state of persistent surprise. I am startled by morning sunshine. Human cruelty continues to stun me. I am undone by a perfectly runny yolk. Why shouldn’t people in my head do the same?

I rely on inspiration and life insists on coming to the page. Once I saw a man pouring a bottle of Perrier onto his windshield while I was walking home. I’m sure he was just using it as a bottle for plain water, but the wanton luxury of it struck me. I ran inside and didn’t even take off my coat, wrote an entire scene around this image, standing hunched over my desk. The stranger became an affluent bully. The Perrier became precious champagne, poured like water to remove bird shit from a window. It has survived many rounds of revisions. Maybe it’ll get cut someday, but if it does, it won’t be due to a lack of electricity.

Draft 2

A wild outline appears

This Swiss cheese document is my first draft because it gets me to what I consider an outline, and into the second draft. I sum up each scene as a sentence, then write in red what’s missing. It reads like more like a bad synopsis or a very boring short story. Every time I sit down to write, something’s either bouncing around my skull already like the Perrier scene, or I pick a red scene that calls to me, and work inside that section for a bit.

(Blurred bc I’m not ready to let you in this house yet.)

This is one way I outrun writer’s block and keep my energy high. But since I’m following where the work wants to go, it takes a long time to feel boxed in. By the time that happens, I know my characters and world so well I typically just need a journaling session to figure it out.

There’s absolutely benefits to outlining first then muscling through scenes in order if your goal is a readable, complete draft. I just don’t find them personally compelling for a work no one asked me for, where I’m the only one living there for 12+ months.

From here, my second draft has me fill in about 75% of scenes. The outline’s still full of red. This is the ‘find out’ section of the adventure and where my crit group has to hear my most ardent complaining. I have to delete and rework large sections. Some of my ‘cut scenes’ documents are 30k words or more. I print the manuscript several times, marking and massaging what’s not reading to my satisfaction.

I’m focused on developmental level edits only at this point. It’s often advised that you must never go back and fiddle with the text til you’re done with a draft, or you’ll never finish. You’ll be too busy fiddling. For me, I’m zooming out and looking at the work as a whole on literal paper with a pen. I can’t change it in the moment. Also, I trust my initial energy has made the prose at least good enough to avoid ratholes.

Sorry trees! I always recycle!!

Draft 3+

Spreadsheet marm

Once I have gone through a few rounds of massaging, about 85% of the book is written. I inevitably start to lose steam. This is when the third/real first draft begins, and when I run to my shadow side, the spreadsheet marm. Oh, yes, she’s been there all along, biding her time. Up to now I’ve maintained a very chaotic and warm energy. And I love that for me. But the next step is a few weeks of space.

I think it was Shruti Swamy in this amazing panel who said, “Future you is your best editor.” I love this idea of co-creating with yourself, so I always try to forget the manuscript exists at this juncture. There are short stories to write, kid pants to mend, fiber to spin. Sometimes, if the vibes are just right, a new book to start.

Once the time has passed, I print and read again with a fresh eye. I follow the same process, reading with a pen in hand. I try to read in as condensed a period as time allows. Ideally, I take a day off dayjob work and devote the entire workday to reading the thing cover to cover.

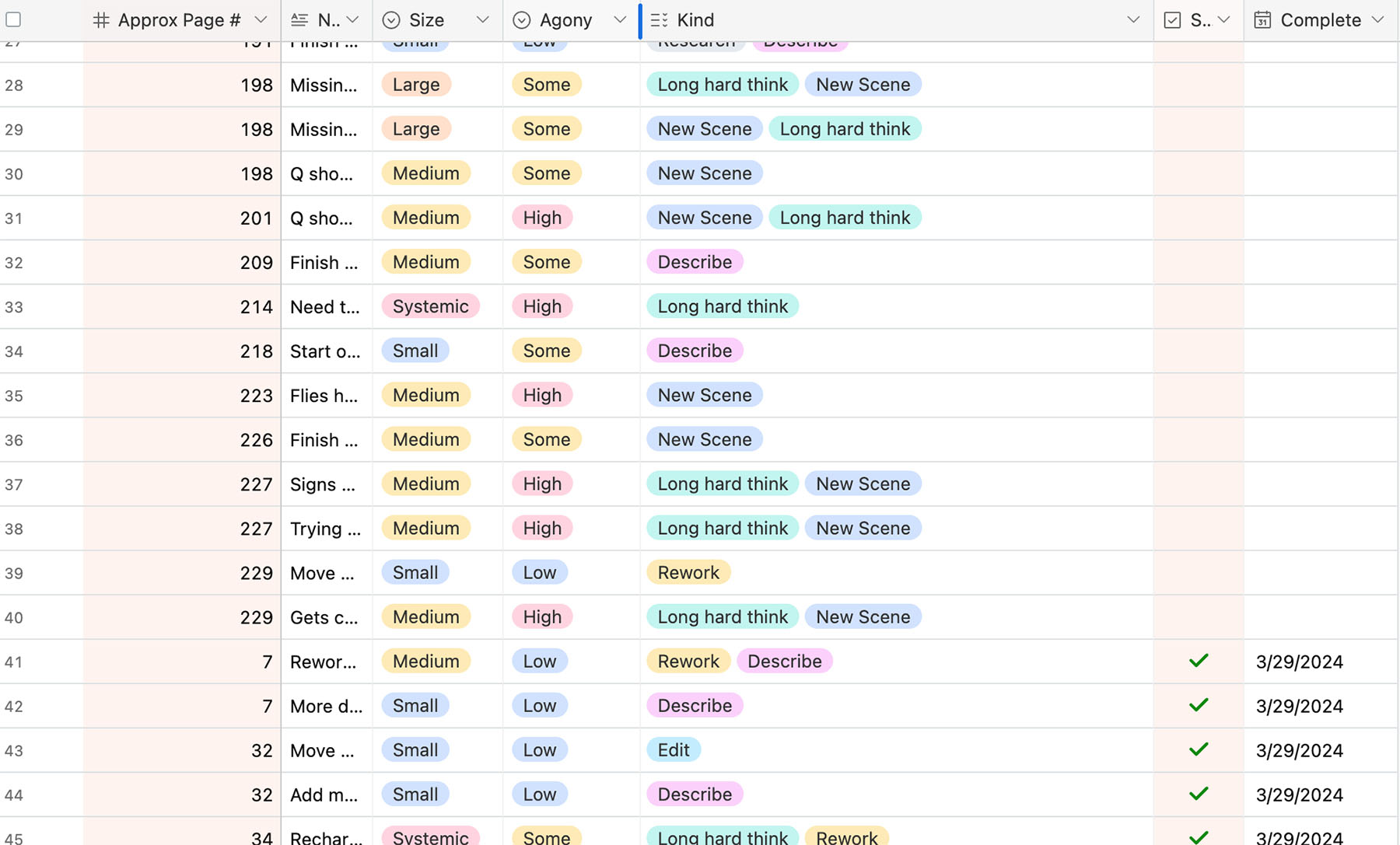

After this, I transfer my edits into a revisions punch list. This format is based on this article, “Revision Sensitive Dysphoria”, which will either give you literal shivers, or you’ll be like, this makes perfect sense for my brain. The TL;DR is: tag each edit with all of the rough description you’d expect. Add a column for time/size, and a column for agony. The agony column is important, because if you use the right tool, you can hide all the particularly agonizing edits when you’re feeling fragile.

When I’m confronting those last scenes I haven’t wanted to write, I ask myself, what would make this fun for me? How can I do the work of making this scene function, while also making it easy to write? I’m convinced readers can tell when you’re not having fun, when you’re not fully invested in the scene.

So then I have a complete third/fourth/first ?? draft. I’ll repeat this last process a couple of times, and then it’s ready for beta reads.

But, why

I fully expect people to read this, shake their heads and think ‘wow, this lady chooses violence every damn day’. Chaos with a spreadsheet. The worst of both worlds. Listen!! You are not wrong. I respect you and your own process. Remember this is all subjective and my personal hot take on how to draft a book. Your process will probably never look like this (unless it does? Where you been?? Please email me????). It took me a while to figure it out because I’ve always frankly been turned off by much of the draft process canon.

I love this quote from Isabel Cañas:

In real life, anyone in my family will tell you that I have all the physical presence of a pocket-sized marsupial, wide-eyed and spindly-fingered. But as a writer, I am an ox. I am muscular and I know it and I trust it.

Even though we have fairly different processes, this captures exactly how I feel when drafting.

Many people advise setting up severe, punishing routines to counter the blank white page. The underlying promise of strict systems is that anyone can set up braces and brackets, pour in a premise, and spit out a work of art. A lot of draft advice is well-meaning, aimed at removing fear. That’s vital, depending where someone is at.

But when you try to remove all fear, you also remove all spark.

A writer needs structure, discipline, and well-laid plans. But none of these things make a good writer. The writer does. The experience, the special verve a person brings into the studio in their heads is the vital piece. The rest can be wrestled and honed.

I’ve seen Carmen Maria Machado lecture a few times, and she always ends up saying some variant of, How do you know it’s good? How do you know it’s working? After a while, you just do. It’s vibes. I know that’s frustrating, but that’s it. The big underlying support under my drafting process is that I have grown to trust myself entirely. Will I get it right on first blush? Likely not, but all problems are tractable. When will my book grow its fangs, its balms, its charms? I’ll know it when I see it.

No matter what method you use, you must learn to trust yourself. You are the necessary sieve that all the work runs through. Use tools to unstick, to gain new perspective, but this is one of the few places in life where you’re unequivocally the star of the show. You’re the one who makes this happen. Your instincts are paramount. Hone them with the things you love. Surround yourself with what inspires you and you will make your way. It’s developing that little whisper that nudges you and says, ‘This is important to me, I don’t know why. Choose chaos, see what happens.’